“Maintenance, Hvidovre,” by Olga Ravn, is a Kafkaesque tale of a mother’s experience during her stay at the maternity ward of a suburban hospital in Hvidovre, Denmark. The story, told retrospectively from the unnamed first-person narrator, recounts the strange unfolding of events at the hospital during her stay–which entails the surreal disappearance of her newborn daughter and inexplicable replacement with a baby boy.

Read literally, “Maintenance, Hivdovre” seems like a dystopian tale of mass baby snatching and substitution. (We learn that a portion of the hospital served as an underground nuclear defense bunker during the Cold War, a setting which adds to the conspiratorial quality of the story.) But the text signals, from the very beginning, the narrator’s likely unreliability: “I’m talking about it now because my husband doesn’t believe me and our two children don’t, either.” Should we, then, as readers?

It soon becomes clear that the narrator is not, in fact, reliable; the text signals throughout that the events cannot be taken literally–whether they appear to constitute a dystopian reality or a conspiracy. Rather, due to complications arising from excessive blood loss after giving birth, the narrator’s account likely stems from a dream-like state, or, indeed, a kind of postpartum psychosis. Ultimately, the doctors are concerned enough to hold the mother and her baby for observation due to the blood loss–but are apparently nescient of the urgency of the situation, one that results, ostensibly, in the narrator’s near-death experience. What follows is a dream-like saga that culminates in an Homeric journey to the underworld, and a return to life.

The destabilizing event occurs when the narrator, who briefly leaves her hospital room where her newborn daughter is sleeping in a cot, returns to find that her daughter is missing. In a panic, she seeks out the duty nurse down the hall, who, oddly, seems utterly unconcerned. Together, they return to the narrator’s room to find the baby asleep in the cot. The nurse reassures the narrator. But the narrator points out that the baby in the cot is now a boy. The conversation has a surreal, misplaced-focus quality:

“She looks different”, I said.

“He’s fine.”

“It’s a girl,” I said.

“No, I think not,” she replied, and undid the nappy so that I could see my daughter’s penis and scrotum.

“I’ve already got two boys,” I said.

“You’ll have your hands full,” she said, now on her way out.

The narrator’s blithe reaction–which typifies her responses to the story’s other inexplicable events–contributes to the dream-like quality of the narrative, and underscores the issue of narrator unreliability.

Things continue to get more surreal; the narrator encounters a series of other new mothers, who shuffle around the maternity ward, zombie-like, asking, “Did you see my kid?” Evidently their babies have been swapped, too. An interesting characteristic of these women is their interchangeability: their almost complete lack of differentiating features and cartoonish stock behavior, including the aforementioned catch phrase. The presence of these automaton-like characters turns out to be an essential signifier that the narrator is descending into an Homeric underworld. (More on this, shortly.)

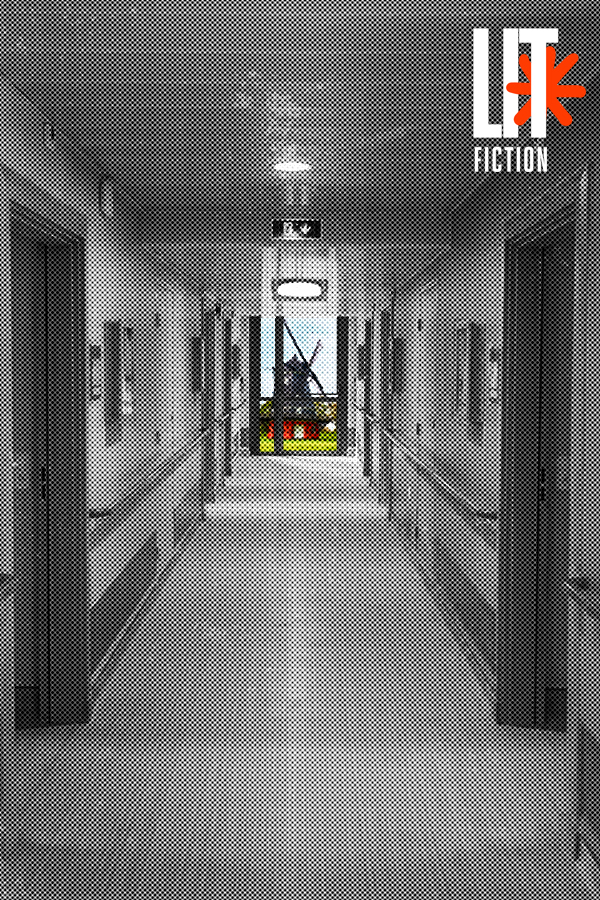

At one point, one of these women shuffles through the exit of the maternity ward, and the narrator pursues her, saying, “You’re not supposed to go out!” The staggering slow-motion pursuit culminates outside of the hospital where, at the end of a maze of hedges, a group of women have assembled and are whitewashing the outer hospital wall with milk of lime contained in buckets. (Note: milk of lime is a solution of calcium hydroxide that has a number of industrial uses, but is also used to whitewash wood. The name derives from the fact that the substance has a milk-like appearance–here, an obvious maternal symbol.) Rather than being baffled by the display, the narrator, out of a sense of duty, picks up a paint brush and joins them: “A strange fog came down around the gable end, whose maintenance was our responsibility.”

The women labour over their whitewashing while they continue to leak postpartum blood. The narrator slips on the slick ground and, when she stands up, her face is coated with blood and lime milk. This Kafkaesque scene marks the nadir of the narrator’s descent. As above, it is no coincidence that the other women appear to be mere simulacra; in the Odyssey, when Odysseus ventures to the underworld, it is a dim and shadowy place. The spirits who inhabit it are described as being witless and bereft even of self-knowledge; indeed, a spirit here is sometimes referred to as an eidolon, or “image”–much less real than the once-living person (source: “Demeter, Persephone, and the Conquest of Death,” from Elizabeth Vandiver’s Classical Mythology). The women at the hospital, the ones engaged in the whitewashing of the wall are, in this sense, aptly characterized.

But like Odysseus, the narrator ascends from her underworld. Note that, thus far, dull colours and diffuse, sterile light (“like bleach”), pervade the narrative–both within and outside of the hospital. A memory springs to her mind:

All of a sudden I thought about my husband at home, the boys. I saw in my mind the unholy mess of their untidied rooms. A monstrous clutter of primary colors.

She ascends, both literally and metaphorically, back to her hospital room. It is interesting that, along the way, it occurs to the narrator that she “…musn’t lick [her] lips” to remove the lime milk deposited on them. This too is telling: in the myth of Demeter and Persephone, it is by eating a pomegranate seed in the underworld that Persephone becomes trapped there; evidently, one musn’t consume anything in the underworld lest one be trapped there in perpetuity.

The doctors discharge the narrator and her newborn baby boy. Her husband picks them up and takes them home.

The story’s concluding paragraph once again evokes the myth of Demeter and her daughter Persephone:

Every year, when May comes around, I wake up at about 4 a.m., confused by the light of the sky, as if the spring night concealed a day. The trees blossom in the street and I look at them through the window. I am an implement, a sweeping brush, who remembers the other child. It’s like happiness.

The “other child” in this case is the baby girl that the narrator did not have, but longed for. In the myth of Demeter and Persephone, a deal is struck with the god of the underworld, Hades, who had abducted Persephone, to allow her to return to the world once per year to usher in spring. Likewise, each spring, the memory of the girl that the narrator never had returns to her. It is not happiness, exactly, but it is close.

Credit: Thanks to Karen Daley for helping to unlock the key to this story!