This week, I’m excited to provide some thoughts on “The Plaza,” by Rebecca Makkai, which appears in the May 8, 2023 issue of The New Yorker.

“The Plaza” invokes the “rags to riches” master plot–but in a modern, ironic manner. The Cinderella of this story is Margie, a 23-year old waitress at a hotel bar in the aptly named town of Stickney, New York; Margie is the twice-crowned “Trout Queen,” winner of the local beauty contest.

Enter Alistair: a handsome, charming Yale man, who has arrived in Stickney with his friends for a jaunt of trout fishing. Upon meeting Margie, though, his objective changes: he avers that the Trout Queen is now the only fish he’ll catch. And he does. Soon they consummate their relationship, and in a sentimental inversion, Alistair henceforth becomes Ally to her, and she Margaret to him. Ally returns to New York City, and shortly thereafter Margaret learns that she’s pregnant. She sets off by bus to the metropolis to inform Ally, who, when she arrives at his office, is ecstatic to see her. This marks the beginning of the story’s middle.

Let’s pause for a moment and take stock. One of the great things about “The Plaza” is the Chekhovian characterization of Margaret. It is clear from the beginning: this is not a typical Cinderella story, and Margaret is not a one-dimensional Cinderella. She suspects, from the start, that Ally is too good to be true; and although her sincere affection for him attenuates her doubts, they never entirely evaporate. Her inner conflict in this regard–her propensity to care for others and her longing to see the best in them, in Ally–creates internal conflict and feelings of guilt. And she is not, herself, inexperienced in random romantic liaisons–despite her characterization otherwise by the Stickney locals. And when she learns that she is pregnant, her thought is to seek out an illegal abortion. (The story takes place shortly after World War II.)

With respect to Ally, as the story progresses, he is revealed to be not just handsome and wealthy, but also eminently human: as a child he was kidnapped and held ransom (due to his being the wealthy heir of a property baron), an experience that still haunts him. Later, he reveals that he served on the U.S.S. Yorktown, a navy vessel that was sunk during the war; Ally watched helplessly as his best friend went down with the ship. And yet, there remains a dubious quality to his character.

When Margaret first meets with Ally in NYC, she immediately suggests an abortion–she has no interest in having a child, her interest is solely in Ally. But he won’t have it; Ally, it turns out, is a Catholic. And yet…getting married is out of the question (it’s too dangerous due to the kidnapping risk, of course). But Ally agrees to a compromise: they’ll get married, in secret. He’ll put her up at the luxury Plaza hotel (owned by his family) until the time comes that they can reveal their marriage and move abroad. And she’ll have the child.

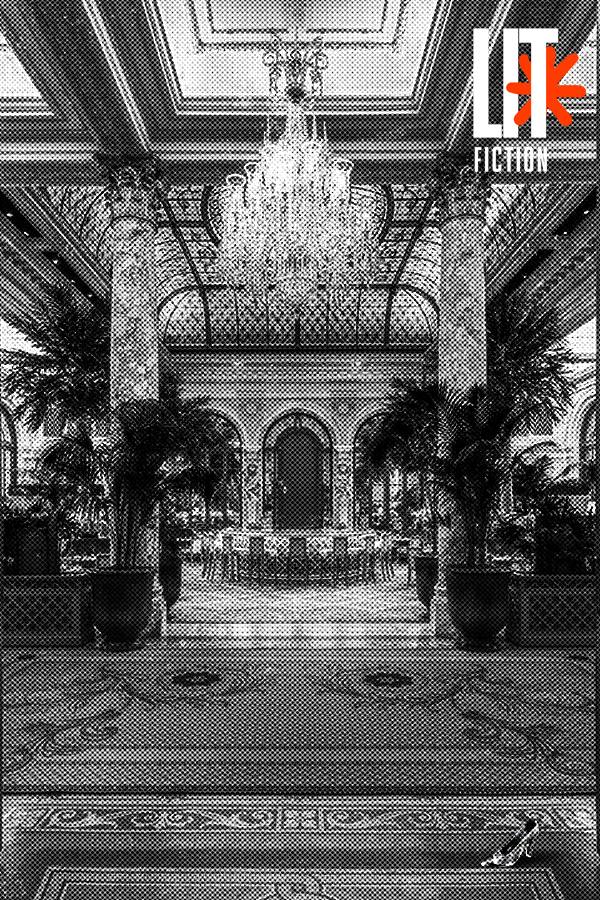

Margaret gives birth, and because of the public constraints on their relationship, she lives a cloistered life in a suite in the luxurious Plaza–a gilded concierge lifestyle–with her child. But she scarcely sees Ally–the one thing she wanted–and the child–the one thing she didn’t–becomes too much for her to handle (being an inveterate “hellion”); and so Margaret entrusts the child’s care and upbringing to the live-in nanny.

The situation further degenerates as Margaret discovers, incrementally, that Ally isn’t what he claims; he is a classic reprobate and the entirety of his pretenses, other than his and his prominent family’s wealth, are exposed to be fabrications. Hence, Margaret was taken for an elaborate ride. Jaded by her experiences at the hands of a manipulative, pathological liar and womanizer, Margaret evolves–adapts–into a shrewder and more manipulative person. Sadly, the culmination is inevitable: her child, this hellion that she never wanted and does not possess even a modicum of maternal affection for, and who has known nothing but room service and the complete absence of discipline, is destined to grow up to become the apex distillation of her physical beauty and her father’s unfettered Machiavellianism.

“The Plaza” is tremendous story in part from the way that the narrator does not hold back from the reader: as noted, Margaret suspects something is amiss from the very beginning, as do we, but her good nature suppresses her instincts and allows wishful thinking to prevail. We go along for the ride, sharing Margaret’s sense of ambiguity, but also the futile hope that the story really will have a fairy-tale ending.

And again, Margaret’s complexity also belies stereotypes. She is inclined to seek an abortion and never does feel–or even feign to feel–affection for her child (which she typically refers to, simply, as “the child” when not calling her a hellion or worse.) Her neglect of the child adds to this complexity in the face of the genuine thoughtfulness and compassion she shows for staff members at the hotel and her younger brother, a hapless drunk, in Stickney. Ultimately, the child, a product of a monster, is, to her, likewise. And yet there is both nature and nurture; Margaret, too, is complicit.

In the end this complexity of character makes it difficult to reach a final conclusion about Margaret. Innocent and duped? A ruthless, uncaring mother? A product of circumstances? Someone who did the best she could in her situation? This is true to life, and the character Margaret achieves a Chekhovian realism–even if not entirely likeable, like Gurov in “The Lady with the Little Dog,” we can at least feel compassion; and whether we admit it or not, we can see something of her in ourselves.

As the story progresses the path increasingly narrows, and ultimately, any hope for a fairy-tale ending is precluded. The story concludes with a resonance, an uneasy feeling–in this ironic retelling of the Cinderella story, the concluding paragraph deftly abolishes much of the ambiguity that was masterfully woven through the narrative. For the child, at least, there is no doubt: she will live Machiavellian ever after.